Two weeks ago, I was looking over the catalogues for the upcoming American auctions. I knew that this blog would be concerned with the auctions’ results, and I had already picked out a title for the post:

“One Hopped, The Other Didn’t.”

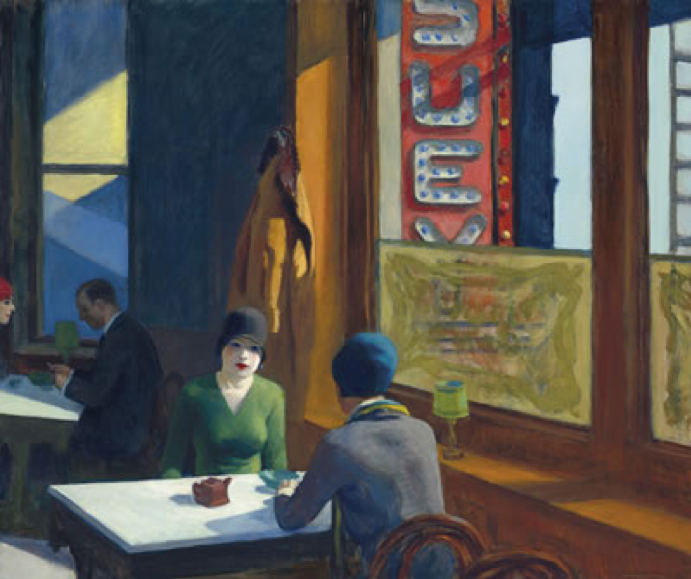

The paintings to be discussed were both by Edward Hopper, one of the great American artists of the 20th Century. Christie’s had what was probably the most important Hopper still in private hands, Chop Suey. The 1929 painting, a large, colorful scene of daily life in New York from the estate of the noted collector Barney Ebsworth, was an iconic piece, everything you could want in a Hopper. The estimate was $70-100 million, about double the previous record for a Hopper oil. Christie’s was on the money in its prediction: the painting was hammered down for $85 million. With the buyer’s premium, the final price was $91,875,000.

Everyone knew that the bidding would be fast and furious for Chop Suey, but I had my doubts about the Hopper that was coming up at Sotheby’s three days later, even though it was approximately the same size as the record-breaking painting. Two Comedians was painted in 1966, the year before Hopper’s death. A man in his 80’s, he had been literally losing his touch; the later works seem cruder to me than the paintings done in middle age. Then there was the subject: two clowns taking a bow. While Hopper painted theatrical and burlesque scenes, they’re not what comes to mind when you think of his work.

When Sotheby’s put an estimate of $12-18 million on Two Comedians, I thought that they were holding on to an unreasonable hope that the painting would somehow latch onto the coattails of Chop Suey. Two Comedians had been offered privately before it went to auction, I had heard, so it was likely that the major customers for a Hopper had already seen it and passed. I didn’t see, therefore, how Sotheby’s could get its estimated price. But Sotheby’s managed to stress the narrative behind the painting: that it was Hopper’s last major oil and that the male and female clowns depicted were symbols of Hopper and his artist wife Jo, taking their final bows to the art world. The story gave a poignancy to what was to my taste an undistinguished painting. The painting was hammered down at just under its low estimate and brought $12,492,200 with the buyer’s premium, so my confident prediction that the painting would fail to sell was wrong.

The auction houses’ good luck generally held for the rest of the lots. Anchored by reasonable estimates, top quality works by the Hudson River and Impressionist schools did very well. The market has pretty well sorted itself out in this age of fewer buyers for 19th century art, and those works’ track records at auction have made setting estimates much less a game of guesswork. But there’s one field where the track record does not make for confident estimates, and that field is works from the 1930’s and 40’s by lesser-known regional artists.

Have you heard of Arnold Wiltz? I have never handled a work by him. Born in Berlin in 1889, he emigrated to America and eventually became part of the artists’ colony in Woodstock. Using a style that eerily conflated Surrealism and Precisionism, he had some success, exhibiting in many shows including a group exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art a year before his premature death in 1937. His works, especially his prints, have since made their ways to museums, and the Smithsonian American Art Museum and the Phillips Collection each have a large oil. In general, however, Wiltz’s works were known only to cognoscenti of the Woodstock School. Only four of his paintings have come up at auction in the past 25 years, and the record price had been achieved by his 1928 painting Along the Seine, which sold for $2,745 at Bonham’s in 2009.

Barney Ebsworth had a 1931 work by Wiltz in his collection, American Landscape No. 3. Christie’s put an estimate of $2,000-3,000 on the piece, probably based on the fact that it was slightly smaller than the auction record holder for the artist. American Landscape No. 3 ended up selling for $50,000 including premium.

So what happened? An American scene is more desirable to American collectors than a European scene, so that may have had an effect on the result. Some bidders may have wanted the bragging rights that come with owning a painting from a distinguished collection, particularly when other works in that collection were selling for millions of dollars. But nothing fully explains why two bidders were willing to chase the work to a mid-five-figure price.

Except, perhaps, quality. American Landscape No. 3 is a remarkable painting, exuding an uneasy tension between a faith that American industrial innovation was going to make our lives ever better and a nagging doubt that something human (indeed, humans literally) had been lost. I have no idea what Barney Ebsworth paid for the painting, but I suspect it was a lot more, in today’s dollars, than the artist’s work had brought at auction at the time. Barney had done his homework in American art, and he trusted his eye before any market vindication. Remember one of my two rules for collecting art: “It’s better to have a home run by a .200 hitter than a pop foul by Babe Ruth.” Among the many home runs by famous artists that Barney collected, there’s also this one by a relative unknown. But it’s a four-bagger for sure.