Unless you’ve been living someplace without newspapers, TV, or Wi-Fi, you have doubtless heard about the painting by Leonardo da Vinci, discussed in this blog last January (Selling Mona Lisa), that sold for $450,312,500, including buyer’s premium, at Christie’s New York two weeks ago.

Dmitry Rybolovlev, the Russian oligarch who is suing the Swiss dealer who sold him this work for $127,500,000, alleging that the dealer overcharged him on several other deals, undoubtedly had the last laugh here.

The sale was surrounded by controversy from the start. Was this a genuine Leonardo? Experts differed. If so, how much of the original painting remained? The work had been heavily restored. In the end, it didn’t matter. Christie’s put on a full court press in marketing the work, holding public viewings of it in Hong Kong, San Francisco, London, and New York. De-emphasizing the Christian theme (it is a portrait of Jesus, after all), Christie’s touted it as “the male Mona Lisa,” brilliantly linking it with what is arguably the most famous painting in the world.

I witnessed some of the hoopla the New York exhibition generated as I arrived to view the American works coming up for sale at Christie’s that same week. I had to push my way past a long line of people who had waited 30 minutes to an hour for a look at the painting. The atmosphere reminded longtime New Yorkers of the 1964 New York World’s Fair, when Michelangelo’s Pietà was on display. Over 27 million people visited the Vatican Pavilion at the fair to stand on a moving walkway and be transported past the sculpture. Christie’s might have benefitted from such an arrangement.

The sale generated headlines around the globe, but it means nothing to the art world. Even assuming the painting was (somewhat) authentic, there aren’t any other Leonardo paintings on the market, and this sale is not a tide that will lift all boats. The only question for me is how the new owner is going to find shipping, insurance, and storage for the painting. No art handlers or art warehouses will want to face the liabilities involved in handling the work, and no insurer will want to be on the hook if the maid hits it while dusting. It will doubtless take a consortium to share the risk. Such an arrangement will be expensive, but that will be pocket change for anyone with the disposable income necessary to purchase the painting.

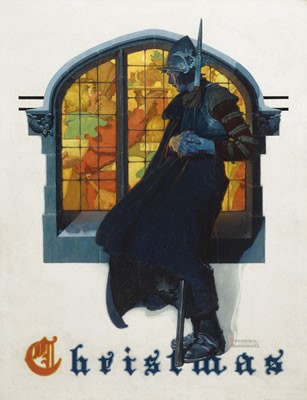

The American sales this month were a replay of the May sales I covered earlier this year. (What Were We Thinking) Hudson River works not of the highest level did not find a buyer, nor did many Victorian works. Western works did well, and Norman Rockwell continued to shine. Or mostly. The painting below did not sell.

I quite liked this painting, which depicted a shivering soldier on guard duty looking wistfully through a window where a jolly Christmas party was taking place. It has that wry emotion that many of Rockwell’s best works have. So why didn’t it sell, when all of the other Rockwells in the sales did well? Because of the caption, in my opinion – Christmas. That irrevocable link with a Christian holiday meant that non-Christians were unlikely to buy the painting. And even for Christians, the link with a specific holiday makes it a seasonable piece.

Perhaps if you had a room of similarly-sized (almost four feet high) Rockwells, each showing a different holiday, the painting would fit in as part of a scheme celebrating the high points of each year. But many collectors or museums would feel silly hanging the painting by itself in July. With a $1,200,000-1,800,000 estimate, it was just too expensive for a seasonal decoration.

When I was growing up, all Americans knew about Grandma Moses. She was on TV and on the covers of Time and Life magazines. Cards bearing reproductions of her paintings sold by the millions. Her story was the stuff of the American dream – a woman born in 1860 to a hardscrabble farming family takes up painting in her 70’s after arthritis prevents her from continuing the embroidery she had always done. She sells her paintings at county fairs (along with prize-winning pickles). Her works were being exhibited in the window of a pharmacy in Hoosick Falls, NY, in 1938 when a collector from New York happened by and bought them all.

Otto Kallir, at the Galerie St. Etienne in New York, gave her an exhibition in 1940. By 1946, her works were being licensed for greeting cards, and Kallir published his first monograph on her work. In 1949 she had an exhibition at the Phillips Gallery in Washington, DC, and the following year a documentary on her life was nominated for an Academy Award. By the time she died in 1961, at the age of 101, she was world famous.

Her paintings recall a simpler time, and there are no references to the hardship and tragedy that stalked farm life back then. (Only five of Moses’s ten children survived their early years.) “What’s the use of painting a picture if it isn’t something nice?” she once said. That niceness spoke to millions of people from Europe to Japan.

She hasn’t generally been collected by museums. Her work is too recent for curators of folk art and much too retardataire for curators of 20th century art. But there may be signs of a change, and her works have sold well in recent auctions. Sugaring Time from 1954 had been estimated at $100,000-150,000 when it was offered at Sotheby’s earlier this month. It sold for $519,000, including premium.

But sales are uneven. There’s a million-dollar gap between highest and lowest prices brought at auction for her large works in the past ten years. Many things – composition, subject, physical condition – go into the disparity in price. I can help explain this to you if you’re looking for a Moses. Let’s talk.