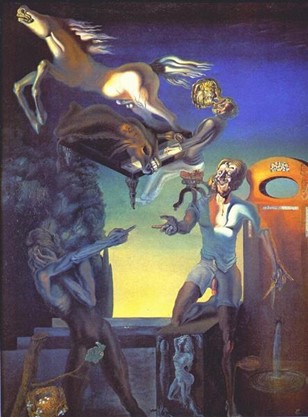

I was on a business swing through the Midwest recently and visited the Art Institute of Chicago to view Salvador Dali: The Image Disappears, the first exhibition at the museum to be devoted to the work of the artist most associated in the public mind with Surrealism. It was a strong show, displaying works from the 1930’s, a pivotal decade in the artist’s career. Paintings like the one below, included in the exhibition, would make his name.

Image courtesy Wikiart.

Born in the Catalonian region of Spain in 1904, Dali received a thorough grounding in Old Master techniques in Madrid at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando. Intelligent, articulate, a tireless networker before the term was even invented, and an exhibitionist with a talent for attracting notice, he went through brief Cubist and Futurist phases after art school before becoming a proponent of Surrealism, a style in which his classical chops could be put to full use. He would become the most important member of the movement.

Art historians and certainly Andre Breton, the founder of the movement who later expelled Dali from its ranks, would disagree with the above statement, but in terms of popular recognition, the verdict is in. The person in the street may not be able to define the term “surrealist,” and they may not have heard of Max Ernst, Hans (Jean) Arp, or Yves Tanguy, but everyone knows the name Dali. St. Petersburg, Florida, is not generally noted as an artworld hotspot, but over 400,000 people visit the Dali Museum there each year. A Dali exhibition anywhere will bring in the crowds, as evidenced at the Art Institute of Chicago.

A visit to the exhibition was an experience akin to trying to look at the illustrations in an art history book while riding in a subway car during rush hour. It was particularly painful for Roberta and me, as it brought to mind a joint Alberto Giacometti/Salvador Dali show we saw last month at the Insitut Giacometti in Paris: small, quiet, and allowing plenty of time to study the details of a painting.

Left-leaning artists such as Picasso never forgave Dali for returning to live in Franco’s Spain. Breton coined the anagram “Avida dollars” from Dali’s name in mockery of the commercial success the artist achieved designing windows for the department store Bonwit Teller and working with Alfred Hitchcock in Hollywood. There’s no doubt that Dali hurt his standing as a “serious artist” with his increasingly eccentric persona, his appearances on late night television, and his voluminous late output (some of which was not really his). He became a caricature of himself, and the ominous images of Surrealism came to seem histrionic compared to the irony of Pop Art or the cerebral rigor of Minimalism. He definitely went out with a whimper, not a bang.

But the general public doesn’t care. Dali’s paintings are not something that could be done by your two-year-old grandchild; they’re “real art.” The imagery that was shocking in 1935 has become familiar through reproduction. Everyone has seen a picture of a melting clock, and they know it’s by a guy called Dali. Like Warhol’s, Dali’s persona has become his own work of art, one with immediate brand recognition. And, like Warhol, Dali’s example has been absorbed by contemporary artists such as Jeff Koons and Damien Hirst. There’s no point in bemoaning his influence or trying to banish him from art history: the votes by the hoi polloi are in. And to adapt a phrase by James Schuyler, if we’re not hoi polloi, what the hell are we?