The Appraisers Association of America is releasing a new edition of its handbook Appraising Art next spring. I was asked to contribute a chapter on appraising the art of the American West. Since finishing my chapter, I’ve been thinking about how different my contribution would have been if it had been written, say, 30 years ago. Much of the advice I give now would have been the same then, such as the fact that you need to compare apples with apples: paintings of European subjects by artists who are commonly classed as Western artists bring a fraction of what their Western subjects bring. A painting of a Prussian soldier by Frederic Remington will bring less than a painting of a U.S. cavalryman. A landscape of the Alps by Albert Bierstadt will bring less than a painting of the Rockies.

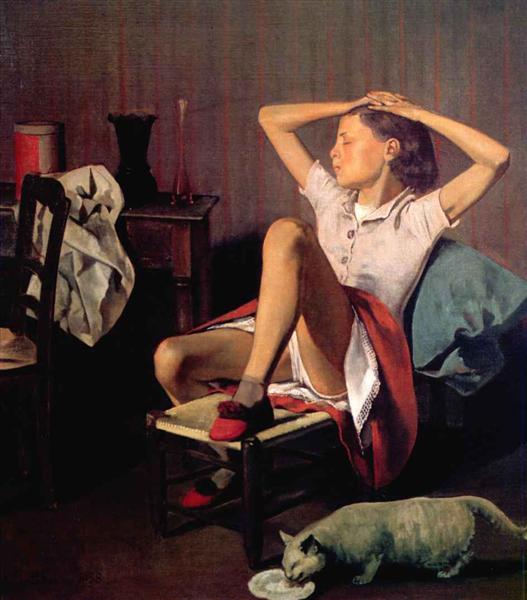

In writing my chapter today, however, I found myself obliged to discuss how recent social changes have affected the value of Western art. Paintings of Native Americans that portray them as bloodthirsty savages are not going to be sought after by museums and many collectors. This rejection of stereotypes applies not only to Native Americans. A painting such as this early oil by Charles M. Russell is practically unsalable today.

Charles M. Russell.

Making the Chinaman Dance.

Black Lives Matter and other movements have changed the landscape for collecting. It’s irrelevant whether an appraiser personally feels that such changes are long overdue social justice or whether an appraiser thinks that PC has gone too far. Just as changes in aesthetic fashion cause the value of a particular artwork to rise or fall, any large-scale shifts in social awareness that reduce the pool of potential buyers for a work of art lessen the value of that piece of art. As appraisers, it’s our job to consider both the aesthetic and the social trends that affect the current perception of art and to boil such data down to reach a monetary value.

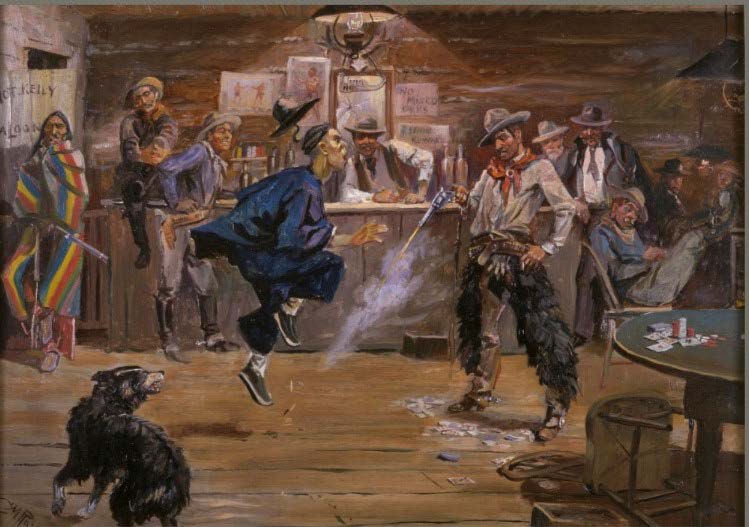

The #MeToo movement has also affected the value of certain types of art. I have written before about how nudes have always been problematic for many American collectors (see previous blogs here) but the uneven power structure inherent in the clothed male artist/nude female model relationship is being challenged as never before. And a female sitter doesn’t have to be nude: in 2017, the Metropolitan Museum of Art received a petition with 10,000 signatures asking it to remove the Balthus painting below from view.

Balthus. Therese Dreaming.

Metropolitan Museum of Art. Jacques and Natasha Gelman Collection.

The museum declined to remove the painting, but I wonder what the organizers of the protest felt should have happened if the museum had acceded to their request. Should the painting be kept in storage, accessible only to art historians or other scholars? Should it be deaccessioned? A similar Balthus painting sold for over $19 million in 2019, and the funds from such a sale by the Met could buy a lot of works of art by women and artists of color. But if the painting encourages pedophilia, if it’s “wicked,” as our Victorian ancestors might say, selling the painting simply allows it to work its wickedness elsewhere in the world. Rather than abetting such transgression, does the museum have a moral duty to destroy the painting?

Such a suggestion raises the hackles of any curator and, indeed, of the liberal public audience in general, of which I count myself a member. Destroying works of art has always seemed a shocking act, whether it’s promoted by Byzantine iconoclasts, Savonarola, the Nazis, or whomever. Nazi artists, ironically, benefited from such revulsion: works of art glorifying Hitler and Nazi militarism were seized by the U.S. War Office after World War II and kept in storage in the United States rather than being destroyed (learn more here). I understand that much of it was returned to Germany in succeeding years.

Can art ever be neutral? Much art theory in recent years has been devoted to showing that it can’t be. Artists aren’t machines; their backgrounds inevitably color what they choose to paint. Their pocketbooks do, too: if they don’t want to starve to death, they had better find someone to pay for their skills, and there’s an old saying about tune-calling by the person who pays the piper.

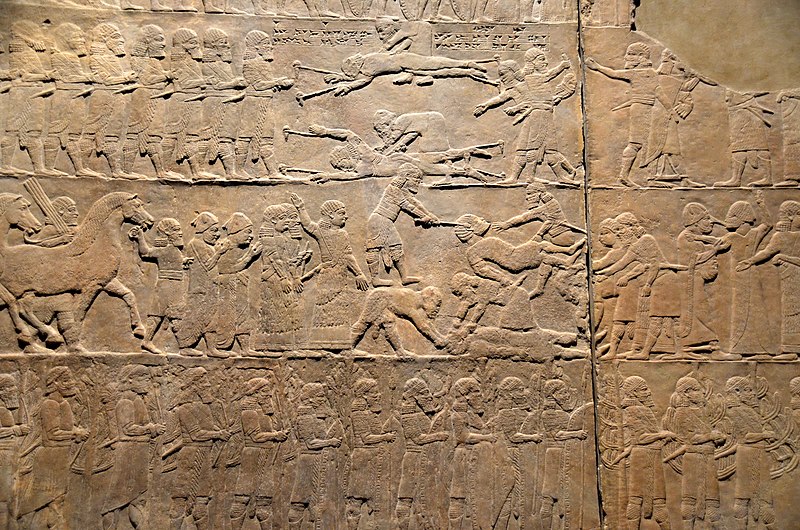

Much commissioned art later finds its way to museums. The British Museum has large holdings of Assyrian art from the seventh century B.C.E. Ashurbanipal, the ruler at the time, was a man of culture and learning, a true patron of the arts. He was also a ruthless tyrant.

Assyrian, Seventh century B.C.E.

Detail from a relief of the Battle of Til-Tuba. British Museum.

The few who can read the ancient inscriptions on this art today can hear the despot boasting of all the people he brought low. For most of us, however, that ancient spilled blood is now just art. If we can avoid causing our extinction as a species for the next 2,000 years, will museum-goers in the year 4023 admire the accurate depiction of the musculature of a charging Waffen-SS soldier in a painting that was saved from destruction millennia earlier? What is the shelf life of depictions of evil? To put it another way, how long does it take for evil to leach away from art?

I’ll leave answering such questions to philosophers and historians. In the meantime, recent injustice is another factor that must be considered when reducing artwork to cold, hard cash.