Often (though not nearly as often as dealers would like) when you’re visiting an art fair or antiques show, you will see a small red dot placed on the label of a work being offered. That dot means that the work has already been sold and thus is no longer for sale.

It’s funny how a tiny red sticker can arouse longing in the human heart. There is something about forbidden fruit that tempts us. I guarantee that if you hold an exhibition of paintings, all by the same artist, all the same size, and all of the same subject, and put a red dot next to one of them, visitors to your show will point to the painting with the dot and exclaim, “Oh, THAT’S the one I would have bought! Do you have any others just like this?”

Dealers can play upon this yearning for the unobtainable. Long ago I knew a dealer down South who would invite a wealthy collector to his home for a formal dinner. During the course of the evening, the dealer would give the collector a tour of his private collection. There would always be a spectacular painting in the place of honor above the fireplace. Let’s say it was a Mary Cassatt.

When the guest exclaimed about what a lovely Cassatt it was, the dealer would agree, “Yes, I’ve never seen a better one.”

“What would you take for it?” the guest would demand.

“Oh, Bill,” the dealer would demur, “That’s not for sale! It’s in my personal collection,” lingering lovingly on the word “personal.”

“But what would you take?” the guest would pursue.

“Bill,” the dealer would protest, “I can’t sell it! That’s Janie’s favorite painting! She’d skin me alive if I sold it! Look, I’ve got another Cassatt at the gallery. It’s almost as good. I’ll sell you that one for my brother-in-law price.”

The guest would reject the proposal, and the conversation would continue, the dealer’s seeming reluctance gradually weakening, until he would finally sigh, “Well, if I’m going to be sleeping on the couch for the next month, you’re going to have to make it worth my while.” A very healthy retail sale would follow.

We want what we can’t have, but we don’t want things that have been passed over. At art exhibitions, in addition to red dots, you will sometimes see a green dot or half a red dot next to a painting. Those dots mean that the work is on hold. Another collector will sometimes put a secondary hold on the work, requesting to be contacted if the person who placed the hold doesn’t purchase the work.

Back in the days when I did art fairs, I always hated putting a hold on a work. The painting hung there, unsellable, for the remainder of the show, and quite often after the show closed and I contacted the person placing the hold, he would say that he had decided to pass. If I had a secondary hold on the work, I knew that I had an uphill battle when I called that person. While speaking to him on the phone, I could almost hear him thinking, “Why didn’t the first guy buy the painting? What’s wrong with it?” More often than not, he would pass as well.

When people asked me to put a hold on a work of art, I learned to tell them that I would put an “invisible” red dot on the work for 15 minutes to give them time to walk around the show and decide whether they really liked the piece and could afford it. After that quarter hour, I told them, the work was available for purchase by anyone. If it remained unsold at the show’s close, I would contact them and we could discuss a sale, but I wasn’t going to take the work off the market now for the uncertain prospect of a future sale.

If you like a painting and you’re a bird in the hand, so to speak, you’d better declare it right then.

Last month I wrote about a Wayne Thiebaud exhibition at the California Palace of the Legion of Honor, and I said that Willem De Kooning was an influence on Thiebaud, even though De Kooning was an abstract artist and Thiebaud was not.

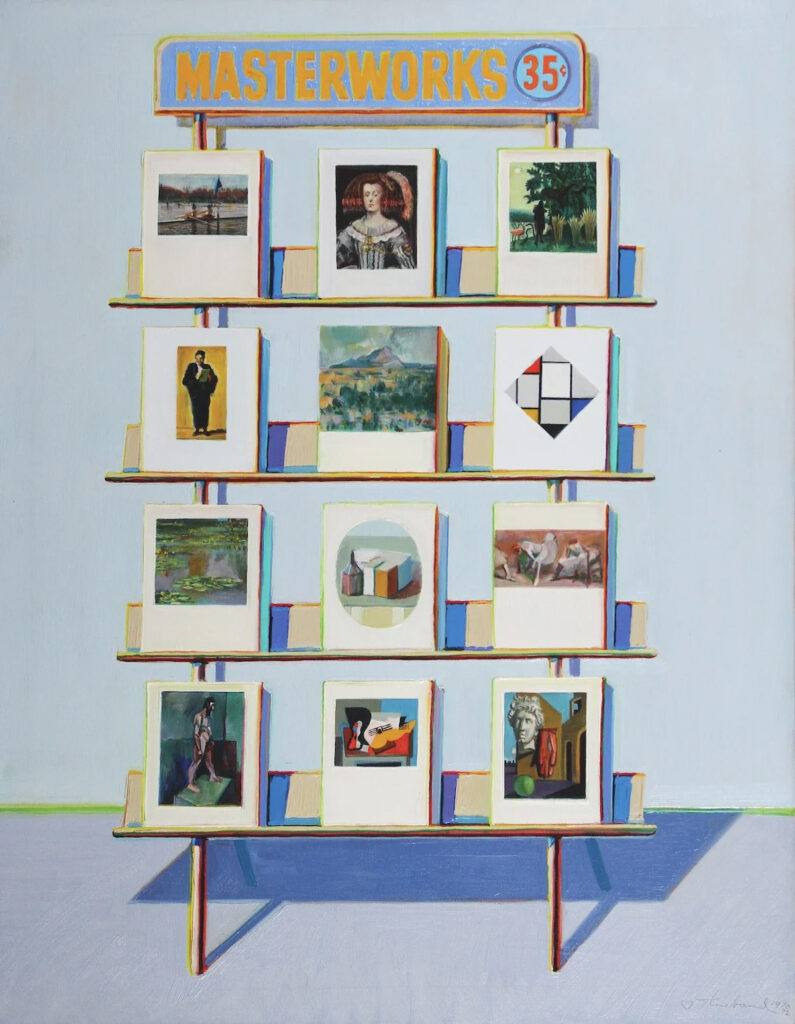

As proof of my assertion, I said that Thiebaud had included a “postcard” of a work by De Kooning in his painting 35 Cent Masterworks, an homage to artists who had influenced his own work. Timothy Burgard, the Edna Root Curator-in-Charge of the American Department for the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco (what a mouthful!), has written to point out that my memory was woolgathering. The painting I mentioned does not include a De Kooning among the works represented. I acknowledge the error and am publicly grateful (though secretly cross) that it has been brought to my attention.

Wayne Thiebaud, 35 Cent Masterworks

© Wayne Thiebaud Foundation / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

What is not incorrect is my assertion that De Kooning was an influence on Thiebaud, dissimilar as the two artists’ work are. Their luscious paint strokes are pure pleasure. The show is still up. Go see it.